In my trek to revisit classic literature (and read the books I was supposed to have read and…didn’t), I’ve finally made my way back to Dickens, specifically to one of his greats: A Tale of Two Cities. I remember trying to read this book in high school. I didn’t make it past the first page. I didn’t know what I was reading and it just seemed…dull. The next time I picked up one of his books was to read Great Expectations in college. I could have had a better instructor, for once again, I found Dickens tedious and the story lacking. But then I read A Christmas Carol as an adult. I read it to my daughter, and I loved it. I think it is a fantastic piece of literature. And I realized that I needed to try my hand (or head, rather) at Dickens again. So, together with some friends and my husband, I decided to read this book. Once again, I’m glad that I read a well-loved classic.

To be sure, Dickens is still a work to get through. You cannot read him halfheartedly or half-hearingly. You have to pay attention and watch for what he is saying. He will lead you along through some witty and extended prose and suddenly you’ll realize you just witnessed someone’s murder. Or the foreshadowing of some momentous event in some spilled wine. You have to watch for his references with double meanings, like the Gorgon, furies, or hooting of an owl. Nothing is wasted with Dickens, though it might seem like it at first blush. His prose is braided with meaning and you have to keep a sharp eye on it or you will miss what he says (and the depth of the story with it). Thus, though this was a challenging read, I am thankful for it. I won’t say that Dickens is suddenly my favorite author, but he grew me as a reader, and I am appreciative of that.

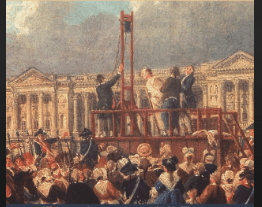

What’s more, I think I understand this time period better than I did before. Writing during the Victorian age, Dickens was born right at the end of the Napoleonic era and thus not long after the Revolution itself. Dickens saw what those who lived during that time could not see (or would not see). He saw the consequences. He saw the wanton destruction, the hate, the vengeance. Yet he also saw that a nearby and much-loved land was on the precipice of the same ills. There is no making the French Revolution look justified, especially not after reading this book. But as the story unfolds, you can understand how long-standing injustice will boil over into wanton destruction, especially among people who have removed every sort of foundation or principle except that of the people, of the “citizen.” There is no truth, no goodness, no beauty. There are no traditions or morals. In such cases, even (and especially) the innocent will suffer. In speaking for La Guillotine, Dickens speaks for the cause as a whole, “It hushed the eloquent, struck down the powerful, abolished the beautiful and good.” And elsewhere, “Before that unjust Tribunal, there was little or no order of procedure, ensuring to any accused person any reasonable hearing. There could have been no such Revolution, if all laws, forms, and ceremonies, had not first been so monstrously abused, that the suicidal vengeance, of the Revolution was to scatter them all to the winds.” What horrors those days were! What horrors led to them! Yet one could not be had without the other.

Though two wrongs do not make a right, as such actions only heap abuse upon abuse, perhaps these events, with other forerunners and consequences, might stir us as Dickens hoped to stir his contemporaries towards stemming the tide of the then-current abuses. And not to simply shirk responsibility but to work in our vocations for the good of our neighbor. One point in this novel that stood out to me is that one cannot simply do nothing. In the storyline with Charles, we come to love him because he does not want to continue the abuses of his ancestors and so gives up his title and possessions with it. Yet he doesn’t initially right those wrongs his ancestors committed, and who he is follows with him. When he gives up his title, he thinks he gives up responsibility. But that is not how responsibility works. It is yours. Thus, his actions draw him back to France to rescue a man he had (unintentionally) neglected. Two wrongs do not make a right, but neither does simply “giving up power.” That power came with responsibilities that he neglected, which is why he and those like him are not the true heroes in this history.

Yet A Tale of Two Cities is not just of England and France. It is not pure historical fiction or social commentary. It is also a deeply spiritual book. While some of the spirituality will come out by way of the Greeks, such as the furies that harry the curator of injustice til they meet their end; or the owl omens that forewarn a coming doom; there is also the deeply Christian vein that runs through the book. There is the faithful wife who prays, despite the railing of the husband; and that husband who speaks as though preaching eventually finds his reform beside a church. There is the faith of Miss Pross, who proves that love is stronger than hate, sacrificing herself in pure love for her foster daughter. There is also the goodness of Lucie, the light of the book, who stands amid the darkness behind her heritage of these Two Cities. And finally, there is Sydney Carton, a man of despised potential who is made anew by a love brighter than the darkness in himself. Here is a man who takes the unjust penalty of another by taking on his form to die in his place, a Christ figure if there ever was one in literature. There is such spiritual depth to this story. I only mentioned a few examples here, and I know I will glean more in future readings.

While it did take me a beat to get into the groove of the story, in the end, I came to love A Tale of Two Cities. Dickens created an incredible plot interwoven with such a depth of meaning that it would take several readings to take it all in. But the story is worth the mental and time investment to read. There are many heartbreaking moments, but even so, there is always that glimmer of hope. While there will be evil rulers, some of which come in the form of Madam Defarge, and weak-willed should-be leaders, like those judges in England or Master Defarge, there will also be those who stand for goodness and truth. There will be those like Charles who try (though often fail) to right past wrongs; there will be those like Lucie who will shine light and life amidst darkness and death, keeping the faith despite all odds. And there will be those like Sydney, who all have abandoned to their whims, yet show themselves to be heroes after all. This is a story of history; this is the story of today. It is a classic. So read this story, giving it the attention it deserves so that you might appreciate all that Dickens has to offer as a writer and as one who desires to convict your soul.

Blessings to you and yours,

~Madelyn Rose Craig